Introduction

The methods in this section can be divided into two types:

- Patient-centred quality improvement approaches

- Generic quality improvement approaches

Patient-centred quality improvement approaches

The evidence base in this area is small but growing; no one approach emerges as the best, and most have something to offer. Some patient-centred quality improvement approaches, such as experience-based co-design, have a more extensive evidence base. This section presents a few of the best-known approaches:

- Facilitated survey feedback

- Experience based co-design

- Patient and family-centred care

- 15 steps challenge

- Whose shoes?

Generic quality improvement approaches and tools

As well as the specific patient-centred approaches, patient experience data can be used as part of other more generic quality improvement methods, which are used for improving safety and clinical effectiveness as well as experience. The following commonly used approaches and tools are included here:

There are a range of quality improvement tools that can be used to support projects. These approaches are not designed specifically to focus on patient experience data, but many healthcare organisations find them extremely useful. This section sets out a few key tools that are commonly used in health quality improvement:

- Model for improvement (PDSA cycles)

- Lean

- Driver diagrams

- Process mapping

- Five whys

- Fishbone diagrams

Two of the best established are the Model for Improvement (developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, using Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles) and Lean (a methodology derived from manufacturing that aims to eliminate waste and boost efficiency, as used by Virginia Mason Hospital in Seattle).

Many quality improvement approaches draw on the Japanese principle of Kaizen (continuous improvement) and use a technique called process mapping to analyse bottlenecks or hand-offs (transition from one staff member or department to another) where problems arise.

Useful reading: Overview of quality improvement in healthcare:

Defining quality improvement

Quality improvement is work aiming to improve the quality of healthcare, which can be divided into three dimensions:

- patient safety

- patient experience

- effectiveness of care.

Quality improvement comprises a wide range of methodologies, approaches and tools, but many involve:

- understanding the problem, with a particular emphasis on what the data tell you

- understanding the processes and systems within the organisation – particularly the patient pathway – and whether these can be simplified.

- analysing the demand, capacity and flow of the service

- choosing the tools to bring about change, including leadership and clinical engagement, skills development, and staff and patient participation

- evaluating and measuring the impact of a change.

Source: Health Foundation (2013) Quality improvement made simple. London: Health Foundation, p 11

Selecting an approach

It is easy to feel overwhelmed by the array of methods available. Advocates for different approaches often argue strongly that their way is the best way. Periodically, a new method will be in vogue, promising a sure recipe for success. Staff may worry that they cannot live up to the examples set by leaders in the field.

There are people who will argue that you should take only one method and stick to it, but others will tell you that the focus on specific tools is unhelpful. A good place to start is to think about what approach generates most interest and enthusiasm from you and your team, and which best matches your existing skillset. You might decide to select one branded approach, pick and mix between several options, or adapt existing methods to suit your needs.

However, we do know that quality improvement is more likely to be sustained where patients and staff are involved in developing, designing and implementing changes, rather than being imposed from the top down.

Source: Health Foundation (2013) Quality improvement made simple. London: Health Foundation, p 12

Our study findings

Some sites more explicitly chose to focus on activities that would boost staff motivation and experience as a route to improving patient experience, through indirect cultural and attitudinal change, and giving staff a sense of feeling empowered and supported.

One team engaged staff by focusing on making simple improvements to the staff experience (such as making changes to the rota system), to win their support and demonstrate how the process would work for patient experience.

Improvement culture

A culture of continuous improvement enables quality improvement to be embedded throughout an organisation. It is easy to become fixated on the individual tools, but the most successful improvers have a mindset that is always analysing the way things are done, and thinking creatively about better ways of doing things. This involves developing new habits – among individuals and across the organisation to support this way of thinking.

Key ingredients for quality improvement

There is mixed evidence for the effectiveness of most quality improvement methods. So far, there is no single quality improvement approach that has stronger evidence than others. Most methods have something to offer, and will work some of the time, in some settings, but will fail without the right conditions in place (Powell et al 2009).

Many evaluations have shown that contextual factors – such as skilled facilitation, time, senior management commitment, resources, and authority for staff to make change – are influential.

Our study findings

Our study reinforced the evidence shown in this section.

Powell and colleagues identify the following as ‘necessary but not sufficient conditions’, regardless of what approach is adopted:

- provision of the practical and human resources to enable quality improvement

- the active engagement of health professionals, especially doctors

- sustained managerial focus and attention

- the use of multi-faceted interventions

- coordinated action at all levels of the health care system

- substantial investment in training and development

- the availability of robust and timely data through supported IT systems.

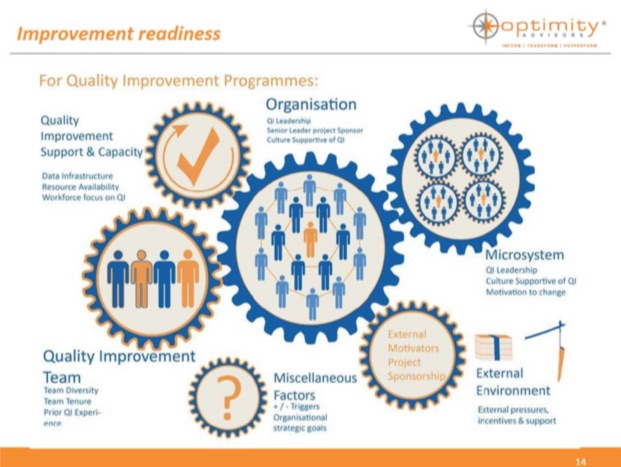

As a result, there has been growing interest in assessing whether organisations or teams or wards are ‘improvement ready’ before starting any new quality process.

The ‘Cancer Patient Experience Survey Buddy Programme’ paired organisations that had high patient experience ratings with organisations identified as having scope for improvement. The idea was for them to work together on improving experience using patient data. The evaluation findings identified several components of improvement readiness:

It is important to pay attention to these organisational and cultural issues, while at the same time finding ways to help those who are not so obviously ‘improvement ready’ and not deter them from trying things out and learning. Overall, organisational culture may matter less at ward level than ward culture and enthusiasm.

Our study findings

Where staff morale was low, sites prioritised project outcomes such as improving staff experience and rebuilding morale.

A pragmatic approach

Powell and colleagues (2009) conclude that a more pragmatic approach may be best: selecting or blending a range of tools and approaches to find the best fit for the staff, task, organisation and environment in question.

The Health Foundation report ‘Skilled for Improvement’ argues that understanding recognised QI tools is important, but that ‘applying the techniques of improvement science alone is unlikely to be sufficient to deliver sustained quality improvements in healthcare.’

It argues that as well as technical improvement skills, teams need to develop a culture of continuous learning and reflection, and a range of ‘soft skills’, including good communication, conflict management, assertiveness and negotiation, time management, stress management, leadership and team-working skills, and organisational and administrative skills.

It also identifies the importance of:

- strong and sustained institutional support

- the influence of key individuals who can either drive projects forward or hold them back

- flexibility to adapt to changing realities

- linking the quality improvement into existing work streams rather than making it a stand-alone project.

The Cancer Patient Experience Survey Buddy Programme suggests that peer-to-peer learning is a helpful way to develop these skills.

Key challenges

This section highlights four key challenges that often arise in the process:

Gaining buy-in

A key activity in a project is to gain the support of the key players who need to sign off on the decision to go ahead and provide the resource (in terms of staff time as well as materials). Their role may involve sharing information about the project, making key decisions, recruiting team members and garnering support from around the organisation. Over time, they may become important advocates for the project, and may be in a strong position to share news about success.

Our study findings

Some sites saw the project as a way to acquire new knowledge and skills. Others saw it as a good fit with their existing quality improvement strategies and practice, a chance to learn from and share with others, and an opportunity to build capacity further at ward level. Sites with these ‘positive’ reasons for taking part generally embraced the project and made progress.

Recruiting the team

Some staff are eager to take part, especially if they are shown the wide-ranging benefits, including improvements to patient but also staff experience, and the opportunity to gain new skills and have a real impact on the way care is delivered. However, some may be reluctant to become involved, especially given high workloads.

Our study findings

It is important to build a relationship and mutual understanding before any demands are made and plan in support with administrative tasks, to minimise the burden on clinical teams.

Team leaders found it helpful to recruit a good mix of people with a range of disciplinary backgrounds and levels of seniority who tended to be able to make things happen more easily – especially if supported by the patient experience team.

Time limitations

Lack of time is a universal challenge for any team attempting this work. Not only are clinical teams working under pressure – shift working can make it difficult to find a time when everyone is in the building at the same time. Nevertheless, building out occasional time to take stock and review progress is beneficial and can also help develop the bond between the team members.

Communication within the team

Given the time limitations, it is essential to find a form of communication that works. Central staff tend to use email but clinical staff may not check their email from one day to the next, so face-to-face may be best. Some teams find it helpful to add the project to the agenda of regular team meetings. Other options include having whiteboards where staff can add thoughts and ideas in real time.

Embedding and sustaining change

Once an intervention has been put in place, it can be a challenge to sustain the momentum, embed the behaviour changes needed and ensure that new staff adopt these changes too. This requires ongoing input. Once this has happened, for some teams the next step is to communicate their changes and spread the changes outside of their clinic or ward, to other parts of the organisation, or even beyond.

Evaluation

There is an argument for ongoing qualitative and quantitative evaluation to be built into all quality improvement interventions to contribute to the evidence base. PDSA is an approach that involves implementing changes on a small scale, assessing impact, improving, testing again and so on. The ‘testing’ stage still involves some form of evaluation but this does not prevent the need for an overall evaluation.

Our study findings

The impacts of some project work may take time to filter through to patients. For example, it is easy to quickly detect the impact of a project targeting call bell use and response times. However, a more diffuse project, targeting staff morale as an indirect route to improving the care experience, may take longer to bear fruit.

Resource

The Health Foundation’s publication ‘Evaluation: what to consider’ provides helpful guidance for anyone wanting to evaluate a quality improvement intervention.

Source: Health Foundation (2015) Evaluation: what to consider. London: Health Foundation.

But are we ready?

There has been growing interest in assessing whether organisations, teams or wards are ‘improvement ready’ before starting any new quality improvement process. But there is a case for getting started even in an imperfect working situation. This guide encourages you to ‘give it a go’ whatever stage your organisation is at. If your team is enthusiastic and wants to make a difference, then you are ready. Even small changes, made locally, can make a big difference to people’s lives.